After reviewing AI regulations in the United States, Canada, and the European Union, this article focuses on the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region.

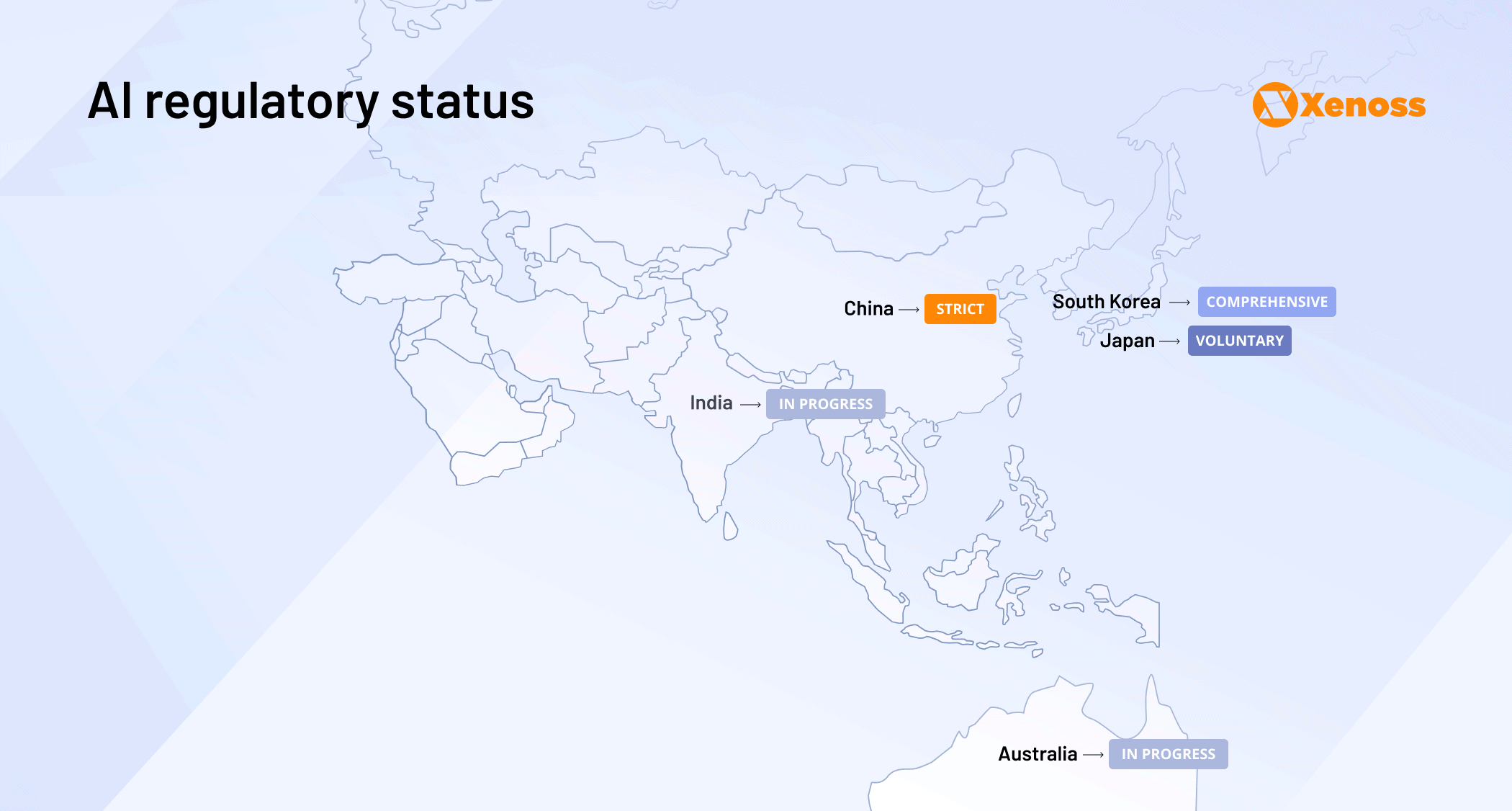

The vibrant APAC region is a patchwork of different national priorities and levels of technological maturity. China has emerged as the leader in the AI race, despite taking the most assertive regulatory approach. South Korea recently passed a comprehensive AI Basic Act, while India and Australia are still working on national frameworks. Japan, in contrast, adopted a light-touch, voluntary AI governance model to encourage innovation.

This deep dive unpacks the latest developments in key APAC markets: China, Japan, South Korea, India, and Australia.

China

China’s AI industry surpassed 700 billion yuan ($96.06 billion) in 2024, with over 100 AI products launched in the past year. It’s currently the only country with an end-to-end industrial chain for manufacturing humanoid robots and a new face at the helm of Gen AI, following DeepSeek’s release.

China takes a more hands-on approach to AI regulation. Its government plays a major role in how AI is developed and deployed, primarily through the Interim AI Measures Act (in force since August 15, 2023), zeroing in on risks like disinformation, cyberattacks, discrimination, and privacy breaches.

All AI platforms must register AI services, undergo security reviews, label AI-generated content, and ensure data and foundation models come from legitimate, rights-respecting sources. Service providers are also held accountable for content created through their platforms. This framework builds on years of groundwork and ties into broader laws like the Personal Information Protection Law and network data security regulations.

Key documents

- Administrative Provisions on Algorithmic Recommendation Services regulate content recommendation algorithms on digital platforms, requiring transparency, user choice to opt out, and algorithm filing with authorities.

- Provisions on the Administration of Deep Synthesis Internet Information Services mandate clear labeling of AI-generated content and require service providers to prevent the misuse of synthetic data.

- Interim Measures for the Management of Generative AI Services, released shortly after the public ChatGPT launch, establishes local rules for foundation models, including data source transparency, accuracy obligations, user protection measures, and security assessments before deployment.

- Cybersecurity Law from 2017 extends to AI services and includes a list of security requirements.

- Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) also applies to AI systems processing personal data, mandating consent, data minimization, and user rights.

Penalties for non-compliance

Compliance is no joke in China because punitive measures are harsh and can include criminal charges.

More severe violations can cost up to ¥50 million (~US$7 million) or 5% of the previous year’s turnover, whichever is higher.

Local regulators can also enforce service suspension or full shutdown for repeated or contemptuous violations. They can also add the offenders to social credit blacklists to restrict access to financing, government contracts, or business licenses.

If the AI product is deemed to threaten national security or leak sensitive data, operators can face criminal investigations, prosecution, and imprisonment.

Japan

Unlike China, Japan has no binding laws or regulations on artificial intelligence. Instead, the government issued several recommendation documents to promote voluntary compliance and ethical best practices:

- Social Principles of Human-Centric AI from 2019 summarize Japan’s overarching vision for ethical, human-centered AI systems, promoting dignity, fairness, and inclusivity.

- AI Governance Guidelines for Business, updated on April 19, 2024, provides practical artificial intelligence risk management guidelines, emphasizing data safety, transparency, and human oversight.

- AI Governance Framework from 2024 integrated earlier recommendations into a unified framework with clear expectations on AI risk assessments and voluntary compliance practices.

All of these laws are also backed by existing privacy protection regulations like the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI), similar to Europe’s GDPR, the Digital Platform Transparency Act, which promotes transparency and fairness in e-commerce and digital advertising, and the Copyright Act and the Act on the Protection of Personal Information.

Japan also established a consultative AI Strategy Council to oversee further developments. In May 2024, the body submitted a draft discussion paper, exploring the need for future AI regulation.

A working group has also proposed a new law, the Basic Act on the Advancement of Responsible AI, which could shift Japan from a soft-law, voluntary approach to a hard-law framework. The proposed bill suggests regulations for some foundation models, reporting obligations, and governmental penalties for non-compliance. The proposal, however, is at a very early stage and still under discussion.

Penalties for non-compliance

Japan doesn’t have penalties specific to AI compliance. However, businesses can trigger regulatory action if AI-powered products breach other laws, such as the APPI or the Copyright Act.

South Korea

South Korea became the second jurisdiction after the EU to pass comprehensive AI laws.

The Basic Act on the Development of AI and the Establishment of Trust (aka AI Basic Act) will take effect in January 2026, after a one-year preparation period.

- The AI Basic Act primarily concerns “high-impact AI” systems used in healthcare, education, finance, employment, and essential services.

- By design, high-impact AI systems must allow meaningful human monitoring and intervention at any time.

- Vendors will have to inform users when they interact with AI-generated content or make decisions.

- All AI risks and controls have to be assessed, documented, and properly addressed.

- Foreign AI companies operating in the market will have to appoint a local representative to handle regulatory communications.

In addition, AI systems are subject to several existing laws, including the Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA), which requires user consent and limits personal data collection scope. The Network Act, which governs cybersecurity and data protection for online services, also extends to AI platforms. The Product Liability Act, in turn, will hold manufacturers of AI-driven products liable for any damages caused by defects like software bugs.

Penalties for non-compliance

The AI Basic Act includes a penalty for non-compliance with the above requirements or failure to set a local representative.

However, more detailed enforcement rules (and perhaps penalties) may follow after the 2026 implementation.

Implementation timeline

South Korean AI businesses have one year to get compliant with the AI Basic Act — implement proper disclosures, conduct risk audits, and improve existing documentation. As the law goes into effect, additional requirements and enforcement practices may also emerge.

India

India is yet to adopt dedicated artificial intelligence legislation. For now, the country relies on a mix of existing laws covering privacy, cybersecurity, and consumer protection.

However, voluntary ethical guidelines exist. The “Responsible AI for All” strategy document, released by NITI Aayog (a national think tank), promotes the principles of:

- Ethical AI development and AI usage to bridge socio-economic gaps

- Privacy and security to ensure the protection of personal data and respect for the user’s consent

- Transparency and explainability in model design, with clear documentation and interpretable outputs

- Cross-sectoral collaboration between the government, industry, academia, and civil society on building a robust AI ecosystem

A follow-up document — The Operationalizing Principles for Responsible AI — further emphasises the need for proper regulatory oversight and ethics by design in AI development.

Yet progress has been slow. India passed an updated Digital Personal Data Protection Act in 2023, which extends data protection principles to AI systems. However, its enforcement will only begin in mid-to-late 2025, with no definitive date yet. The government is still setting up the Data Protection Board of India, an enforcement authority that will operationalize parts of the Act.

Similarly, the proposed Digital India Act is still undergoing iterations. Some proposals include measures for high-risk AI systems to ensure algorithm explainability and establish fairness audits. New provisions may also be added to safeguard consumers from AI-driven misinformation and deepfakes.

At the sectoral level, several existing bodies oversee AI use. The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) oversees AI-driven intermediaries under IT rules but mostly practices a “light-touch” approach. In 2024, MeitY issued new content labeling requirements for all AI-generated content and mandated companies to obtain government approval before launching or promoting AI models that are still under testing or likely to produce unreliable or inaccurate content.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) have published guidance on mitigating AI risks, but neither imposes any direct regulations.

Implementation timeline

The Digital India Act is still in the consultation and drafting phase; no final version has been presented to the Parliament. At the same time, the updated Digital Personal Data Protection Act is yet to come into effect.

Until then, AI governance relies on frameworks like the IT Act 2000, the new Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA), and sector-specific advisories.

Australia

Australia has no AI-specific law yet, but is actively working toward an AI regulatory framework. In 2024, the Australian Government released a proposal paper outlining mandatory “AI guardrails” for high-risk AI applications in healthcare, employment, finance, and education:

- Risk assessments before high-risk AI system deployment

- User disclosures when interacting with AI content and decisions

- Human oversight mechanisms for monitoring, intervention, and decision overriding

- Legal accountability measures for harm caused by high-risk AI use

- Data quality standards for AI training and operational datasets

- Rigorous testing to minimize biases and prevent discriminatory impacts

- Sufficient security protection against adversarial attacks and technical failures

- Explainability mechanisms to give disclosures to users and regulators

At present, these guardrails are recommendatory. However, they may become part of new privacy, consumer, and sector-specific laws as the government seeks to upgrade its regulatory framework. During the recent Paris AI Action Summit, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) signed a joint declaration on building a reliable governance framework for trusted AI, signaling that further developments may be underway.

But for now, AI companies can only be held liable under existing laws like the amended Privacy Act 1988 and consumer protection rules from the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) authority. The healthcare sector, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), extends its regulations to AI-powered solutions, while ASIC governs AI use in the financial domain.

Implementation timeline

Until comprehensive AI regulations are introduced, regulators like OAIC and ACCC will continue to govern AI under existing laws. Those shouldn’t be taken lightly, since a single violation of the Privacy Act can lead to fines of AU$50 million or more for severe breaches.

Bottom line

The Asia-Pacific region presents a diverse and fast-evolving regulatory landscape for AI. China sets the bar for assertive government control, enforcing strong compliance and penalties. Japan opts for a more innovation-friendly, voluntary approach, though it may pivot toward mandatory rules shortly. South Korea has passed a landmark AI law, with implementation set for 2026. Meanwhile, India and Australia are building the foundations for national frameworks, but rely for now on existing sectoral and privacy laws.

For companies operating across APAC, this means navigating a regulatory patchwork: strict registration and labeling in China, voluntary risk assessments in Japan, and soon, formal compliance obligations in South Korea. While convergence isn’t likely in the short term, the global direction is clear: more transparency, stronger data protection, and accountability mechanisms tailored to high-impact use cases.

As APAC continues to shape its AI governance models, organizations that act early to build flexible, compliant-by-design systems will be best positioned to adapt—and lead—across this complex region.